Public exposure to government missteps has steadily mounted. Just over a week ago, officials admitted a “communications mix-up” caused the UK to miss a critical deadline to join an EU scheme for acquiring additional ventilators — a glaring failure that exposed the cracks beneath the polished surface.

Until then, No. 10 had appeared ahead of the curve, buoyed by a new Chancellor adept at managing the public message. But such fiscal and rhetorical sleight of hand can only cover so much before the illusion fades.

Let us recall that as early as January 2020, governments worldwide were aware of the severity of COVID-19. Countries that responded quickly — taking decisive early action — now find themselves better positioned to manage the crisis. While no one claims the challenge is simple or painless, these nations report proportionally fewer deaths and have deployed strategies such as lockdowns, clear public health advice, and significant economic stimulus packages to cushion the blow.

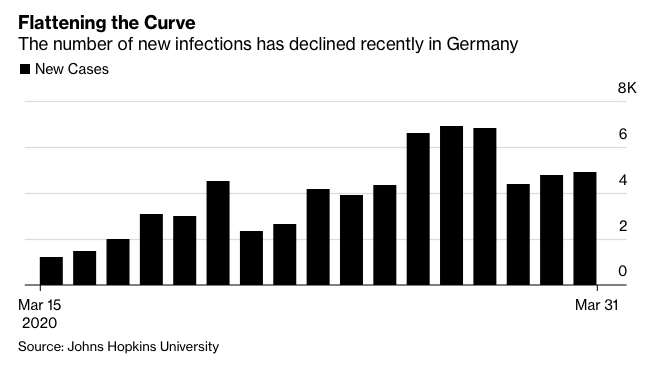

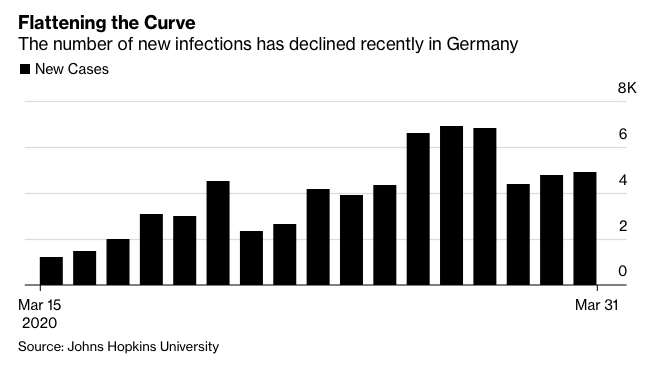

At the heart of effective response lies mass testing — a vital tool to hunt down the virus, trace its spread, and impose targeted restrictions where necessary. Germany epitomises this approach, with its rigorous testing programme enabling swift, informed decision-making and a more controlled outbreak.

Herein lies a stark contrast in leadership styles and preparedness between Germany and the UK. German Chancellor Angela Merkel, armed with a doctorate in quantum chemistry, possesses the scientific literacy and intellectual discipline to understand and trust the counsel of experts. Germany benefits from a well-resourced healthcare system and a robust industrial base, equipping it with both the capacity and capability to mount a measured response.

In the UK, by contrast, we have a Prime Minister better known for his populist rhetoric and a penchant for a “pound-shop Churchill” performance than for grounded, evidence-based leadership. This style may rally certain segments of the public but does little to inspire confidence in the complex task of pandemic management.

The consequences are tangible and grave. The government’s hesitancy to ramp up testing, the delayed lockdown, and the absence of clear, consistent communication have all contributed to a response less effective than it could have been.

This is not merely a question of political style but one of lives saved or lost. As the crisis unfolds, the gulf between countries that acted decisively and those that hesitated becomes clearer, with real human costs.

In a moment that demands clarity, competence, and humility, political theatre and spin will not suffice. The UK’s future will depend on learning from these missteps, embracing scientific expertise, and rebuilding public trust — all of which begin with honest accountability.

For those willing to look beyond the headlines and memes, the real story is far from over.

From January to March 2020, the Johnson administration was marked by an unusual blend of unorthodox advisers — a self-styled cadre of “weirdos and misfits.” These mavericks, operating with skepticism toward the traditional Whitehall civil service, appeared to fixate on a controversial and deeply flawed strategy: herd immunity.

It has been widely reported — though the veracity remains debated — that Dominic Cummings, the Prime Minister’s chief adviser, suggested a brutal calculus: “if a few old people die, so be it. The priority is to protect the economy.” Whether true or not, the broader narrative remains clear. During this critical period, Boris Johnson publicly spoke about herd immunity, seemingly advocating for the virus to be allowed to “take it on the chin.” He famously encouraged handshakes in the early days, downplaying the severity of the threat and treating COVID-19 as little more than a seasonal flu.

To understand why this approach was so perilous, we must revisit the concept of herd immunity. Herd immunity occurs when a sufficient portion of a population becomes immune to an infectious disease, either through previous infection or vaccination, thereby reducing its spread. For diseases like measles, herd immunity protects vulnerable individuals because the virus cannot propagate effectively once a critical mass is immune.

Johnson’s inner circle apparently believed that allowing the virus to sweep through roughly 60 per cent of the UK’s population would confer herd immunity and end the epidemic naturally. This “let it run” strategy ignored a fundamental reality: unregulated viral spread risks overwhelming healthcare systems with catastrophic consequences.

With a population of approximately 70 million, 60 per cent equates to 42 million people. Even with a conservative 1 per cent mortality rate, this implies 400,000 deaths. Current estimates suggest the COVID-19 mortality rate in the UK hovers closer to 5 per cent, potentially translating to a staggering 2 million deaths under this scenario.

The moment of reckoning came as the severity of the virus’s impact became undeniable. Johnson appeared to recognize the catastrophic consequences of his initial approach — the misplaced confidence in a herd immunity strategy promulgated by his “weirdos and misfits,” whose disturbing fascination with eugenics seemed to overshadow the immediate imperative to save lives.

While many governments were already mounting decisive responses, Johnson remained caught up in a world of privilege and university nostalgia — social circles where discussions of “progressive eugenics,” a term coined by fellow Tory Toby Young, were not unheard of.

Faced with mounting criticism and an escalating crisis, Johnson shifted gears, retreating from public scrutiny as he isolated due to his own infection. From his confinement, he sought to regain control of the narrative, proclaiming that “testing would unlock the puzzle.”

The question remains: how many lives might have been saved had he acted decisively from the outset, heeding scientific advice rather than political ideology? The early months of the pandemic exposed a fatal combination of complacency, misplaced priorities, and political calculation — a lesson with profound implications for public trust and future crisis management.

Faced with mounting criticism and the stark reality of the crisis, Boris Johnson abruptly shifted course, backtracking on his earlier policies while retreating from public view. Now self-isolating and effectively shielded from scrutiny, he has placed himself beyond direct accountability. From this isolation, he continues to issue proclamations—his latest being the assertion that “testing would unlock the puzzle.”

Firstly, this is not some inscrutable puzzle—it is a virus. Like all viruses, the only way to defeat it is to track it relentlessly and eradicate it. And to do that, you need one critical thing: information. That information comes solely through mass testing.

Secondly, Johnson now appears to be spinning out of control, repeating phrases and ideas he clearly does not grasp. This approach echoes the Trump playbook—repeat a claim often enough, and some will accept it as truth. In times of fear and uncertainty, people crave reassurance, and many will cling to any narrative that offers hope, however unfounded.

Yet, the stark reality is that the UK lags behind other nations in testing capacity. Take South Korea, for instance. With a slightly smaller population, South Korea operates twice as many testing laboratories and processes roughly two and a half times the number of tests per week. This disparity underscores the missed opportunities and the urgent need for a clear, science-led strategy in the UK.

At the end of the day, people have died as a direct consequence of Boris Johnson’s misjudgments and mismanagement. While thankfully the majority will not face the heartbreak of losing a loved one due to these failings, the human cost remains undeniable. Any reasonable observer disillusioned by Johnson’s handling of the crisis may be forgiven for questioning his fitness to lead on the world stage once this ordeal has passed.

This critique targets his policies and competency, not the man himself. I sincerely wish Johnson and his partner a full and speedy recovery.