Sitting behind the bluntness of North East folk and our landscape of gradually diminishing industries was a sense of identity, connectivity; some would say community and others would say solidarity. My parents, like their parents before them, were driven by a natural desire of love that is shared by parents from across the globe, for their children to live a better life to which they had experienced. It was a generation that had witnessed at first-hand war on home soil, the effects of absolute poverty, created a welfare system and the movements to resist the unacceptable forces of privilege. Politics for my parents evolved from the experience of actual daily life rather than top-down, textbook theories, but organic, imperfect, slow and at times frustrating. It was a pragmatic type of socialism that built social spaces. Social spaces with stable job’s, the council house I was brought up in, The Worker’s Education Association where I took evening courses, the working men’s club my father frequented, the bingo hall my mother enjoyed, the annually planned visit to the seaside and the Christmas pantomime by a local club.

Sitting behind the bluntness of North East folk and our landscape of gradually diminishing industries was a sense of identity, connectivity; some would say community and others would say solidarity. My parents, like their parents before them, were driven by a natural desire of love that is shared by parents from across the globe, for their children to live a better life to which they had experienced. It was a generation that had witnessed at first-hand war on home soil, the effects of absolute poverty, created a welfare system and the movements to resist the unacceptable forces of privilege. Politics for my parents evolved from the experience of actual daily life rather than top-down, textbook theories, but organic, imperfect, slow and at times frustrating. It was a pragmatic type of socialism that built social spaces. Social spaces with stable job’s, the council house I was brought up in, The Worker’s Education Association where I took evening courses, the working men’s club my father frequented, the bingo hall my mother enjoyed, the annually planned visit to the seaside and the Christmas pantomime by a local club.

Yes, there were those amongst us who held views and opinions that were considered aberrant, but sadly these type of people exist in all walks of life, cultures, and classes. Those from outside an immediate community often have a self-interested tendency to point the finger elsewhere to avoid attention to their behaviour and to reinforce their imaginary stereotype. In our social spaces, aberrant views could be challenged, filtered, and the values of respect, individuality, social justice and responsibility became interchangeable meanings and refined haphazardly through discussions and blunt observations.

Growing up in the 1960s & 70s in these industrial heartlands the Labour Party, its wider shared values held influence in everyday life. My decision to join the Labour Party in 1977 at age 16 was not in reaction to the election of Margaret Thatcher, far from it. It was in my DNA and a decision born out of my class, but it has not been a journey without frustration or questionable loyalty. At its worst, it can become self-indulgement and eat itself with voracity, but at its best, it is a force for good and can change lives for the better. It is a journey that has witnessed me join picket lines. Enabled me to forge everlasting friendships, participate in endless meetings on the most microscopic detail. Deliver leaflets, be elected as a councillor, play a small part in improving the lives of the people I represented, seek nomination to become a Member of Parliament, become a silent member and witnesses the neverending cycle of highs and lows revolve on its axis again, and again.

No Class, Seriously?

Since the 1990s the Labour Party has seemed more comfortable with an increased emphasis on the politics of identity rather than the profound inequalities between the wealthy and poor. As a result, inequality increasingly became a technical statistic to be measured and benchmarked. The flesh and bones relationship between people and their role in society, which focuses attention on class seemed to become unfashionable.

Some political thinkers even went as far as to suggest that class no longer mattered and that we were moving towards a classless society. There is little doubt that this thinking informed the emergence of ‘new’ Labour, which central ethos was one of pursuing ‘aspiration’ which slowly withered credibility given the lack of progress in turning around the economic misfortunes in Labour’s heartlands. Immigration and the free movement of people across international borders have had a further detrimental impact on the plight of working-class communities, but to raise any concerns immediately draws criticism of being intolerant, thick and racist.

It is working-class communities who have historically and continue to be the point of integration for those seeking new homelands. It is also working-class communities faced with the consequences of the under-resourcing of resettlement, which are subject to the draconian effects of austerity.

Given this can it be any surprise that a minority within working-class communities who wrap themselves in a life of bigotry and self-loathing are easy pickings for the dark forces of the extreme right peddling their lies that people from far away land with dark skin are grabbing local jobs and sponging off the welfare system. The fact that the richest countries in the world have historically been the recipients of immigrants should be enough to dispell the lie, but racism and bigotry are not logical. The industrial heritage of the North built on work, skilled trades, production, and selling goods runs deep. Town centres and villages, which were devastated following the collapse of manufacturing genuinely hoped that ‘things can only get better’, but increased expenditure in public services was not, is not, and never will be an adequate replacement for stable employment and a fair wage.

If Labour is no longer capable of understanding this and more importantly be competent to do something about it through a robust industrial strategy, then why should working-class communities invest their faith in a party that does not invest in them? The seed that Labour was fast becoming southern, London-based, out of touch with its working-class communities and more interested in defending the plight of specific interest groups was not difficult to sew. The political vacuum in working-class communities has created a breeding ground for a toxic mix of rightwing, nationalistic, hate-filled and reactionary politics. The myth that class no longer exists is quite staggering given in 2017 we live in a world that has never been so unequal regarding wealth, power, food, safe shelter, education and security. This level of inequality between the wealthy and poor has not happened by accident.

A systematic programme of economic, social and environmental policies have deliberately destabilised and eroded a whole way of life, as well as forcing a wedge between people who only have their labour to sell be they a computer programmer, street cleaner, bricklayer, or nurse. Divisive policies designed to pit families and communities against one another in an endless downward spiral of competition. Those pushed to the sidelines have their lives constantly disrupted by the state through an onslaught of ever-changing benefit rules, skills retraining, housing and welfare programmes, which are deliberately designed to disempower and humiliate.

Local to global

The industrial working class is a global, fragmented and impoverished phenomena. According to The United Nations, Human Development Report, the richest 20% receive 86% of the world’s gross product. The middle 60% get 13% while the poorest 20% receive 1%. Meanwhile, more than 20,000 people a day die from hunger-related diseases, yet we produce sufficient food to feed everybody on earth.

In the UK the poorest fifth of households has 6% of national income after tax, while the share held by the richest top fifth is 45%. So regardless if employed in the sweatshops of Indonesia, assembling mobile phones in China, a technician in a UK nuclear power, or whatever social position, you place yourself, the reality remains that if your economic existence depends on you selling your labour, then homelessness is only a handful of paychecks away. These extremes in poverty are not only tolerated but are now part of the natural order of managing economies.

Destabilise, isolate and instil fear

The dark forces, which our grandparents and parents fought against now cast their shadow across the globe into working class communities regardless of race, gender, sexual orientation, disability or faith. It is an insatiable machine of greed, which knows no bounds. Its only purpose is to absorb as much resource as possible for those it serves, who are increasingly becoming the new elite citizens of the world, able to move across borders with impunity with their capital in search of safe tax havens, secret banking arrangements and minimum regulation. Their only nemesis is being held accountability and the risk of losing their wealth. It is the same dark forces, which are once again turning their attention to home shores under the guise of populist and nationalist movements, partly due to the instability they have caused in far away places, which has facilitated popular resistance on one hand or fanatical faith-based terrorism on the other.

Organisation’s capable of threatening their status must be owned, controlled or destabilised be it, political movements, The European Union, trade negotiation bodies, or even the United Nations. Elected government, which should provide a platform of accountability increasingly resembles a game show where politicians can sliver with ease from the responsibilities of a nation to dance routines on light-entertainment programmes, while a Member of Parliament is shot dead on our streets by a political terrorist. Hate based entertainment is parading the poor through ghoulish poverty porn shows filled with a never-ending diatribe of stereotypes to be laughed at and repulsed. We have increasingly become immune to the horrors of disasters, and even the footage of dead children being washed up on the shores of Europe like discarded litter is the new undeserving poor.

The optimism initially offered by social media to bring people together has turned into a self-indulgent pantomime of pouting selfies, sexualisation, food envy, cats, dogs and throw away memes celebrating trivia. Political exchanges through the likes of Twitter often slide into derogatory language, death threats and degrading images feeding a narrative that nobody cares or should be trusted if they are in need, different or vulnerable. Protected behind the unaccountability of the keyboard prejudices are recycled time and time again, like a windmill grinding away, unable to move from the foundations it is anchored.

A report by US psychologists suggests that more than two hours of social media use a day doubled the chances of a person experiencing social isolation. The report claims exposure to idealised representations of other people’s lives may cause feelings of envy. The research team questioned almost 2,000 adults aged 19 – 32 about their use of social media. Professor Brian Primack, from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, said: “This is an important issue to study because mental health problems and social isolation are at epidemic levels among young adults. We are inherently social creatures, but modern life tends to compartmentalise us instead of bringing us together. While it may seem that social media presents opportunities to fill that social void, I think this study suggests that it may not be the solution people were hoping for.”

Resistance is not futile, but it needs alliances

Every single life affected by poverty is a stain on our humanity, but we increasingly look as if we are willfully surrendering to blind materialism while declaring ourselves powerless as poverty levels creep up, homelessness increasing and the dark hand of hunger is once again knocking on the doors of many families in the UK. Those prepared to challenge this continuous drift into the abyss are looked upon with suspicion or denounced as part of the liberal elite.

Politics and social attitudes, like an economy, works in a cycle. Alliances come together when people experiencing poverty or injustice can align with people who are naturally compassionate, alongside those who intuitively know when something is far from fair. The conditions for change then become prevalent. The economic uncertainty caused by Brexit, the ongoing degradation of local services like parks and open spaces, care for our elders and vulnerable young, libraries, the current crisis in the NHS and the growing levels of poverty in the UK these conditions should be ripe for the forging of alliances. While no single political party has a monopoly on caring, and after almost a decade of austerity, the Labour Party should be at the helm of forging this alliance. It is not.

Oh, Labour were art thou?

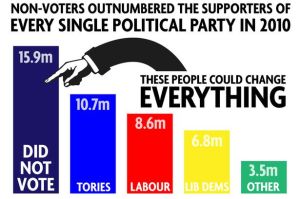

At the moment the Labour Party is obsessed with talking to itself and in danger of becoming fixated with its membership of 600,000 rather than being a champion for 15 million people. The left of the Labour Party continues to recycle the narrative that increased industrial strikes, grass-roots campaigns and local councils refusing to set legal budgets will somehow ignite and build the working class resistance to fight back against capitalism. This narrative represents the type of politics, which in 2017, is more likely to repel most working people given they are not the uniting force they were 50 years ago.

While seeking to tackle tax evasion will always be popular trying to create an alliance on the back of just committing to increase public sector borrowing, spend and state ownership is not likely to attract sufficient support for two reasons. The first and most difficult is that for a lot of people their experience of and loyalty to the public sector is not positive. The second is the perception of economic mismanagement caused by too much borrowing by the last Labour Government.

Poll after poll, beyond any, reasonable doubt has indicated that Labour is not trusted economically even in working-class communities, but like a broken record stuck on maximum volume, those on the left resemble a Victorian missionary with little to offer outside the scripture and doctrine handed down to them.

Those on the right of the Labour Party are equally constrained given they have swallowed and continue to eat the economic principle of the deregulated free global market. The very economic policy, which has destabilised, so many working-class communities.

Blurred vision

A manifesto based on theories and a historical perspective is unlikely to rebuild the Labour Party’s fortunes and restore trust north of the border. The fundamental problem runs much, much deeper given neither wing of the Labour Party can look, think and breath beyond the shadow of Tony Blair and New Labour. No debate can be entered into without, in due course, reference back to Blair regardless if he is considered a demon or saint. Lord Peter Mandelson (a new Labour advocate) has been reported to say that he works every day trying to overthrow the current leader of the Labour Party.

The Labour Party, for good or ill, needs to live with its recent history, understand it, learn from it, leave it behind, stop talking about it and focus on the present and future. After all, why should the general public believe in a party that does not believe in itself? The truth is there is no easy way forward for the Labour Party, or indeed a centre-left perspective given there is nothing to give traction for the holding of a broad alliance together outside the anti-austerity agenda and that alone is not sufficient.

Life

Maintaining and encouraging a mixed market economy, which promotes enterprise, protects the environment, delivers robust public services and tackles innate economic and social inequality should provide the foundation, but the thinking needs to go outside the usual comfort zone of the Labour Party. Socialism in 2020 cannot simply be about the refinancing of public services, delivered through monolithic state-run departments with professional bureaucrats sitting at their helm. It must be about the design of personal services, tailored to the needs of the recipient who must hold the decision-making.

To achieve this requires coherence in leadership, able to paint a compelling vision, communicate it and then forge the necessary alliances to make it happen. Being honest, principled and decent are virtues all leaders should possess, the norm, alone they are not enough.

Not since the 1940s has there been a need for a coherent political response to the current state of affairs. Speaking like this at the moment to my fellow Labour Party members can at time feel like being in labour.

Meanwhile, Prime Minster Theresa May, aware of the tipping point taking place has nudged the Conservative towards appealing more directly to a minority of traditional Labour voters and thus building her alliances across social classes. Her stay is likely to be short given the obstacles she will need to steer the Tories through their European dilemma and waiting in the wings are far more sinister and reactionary forces. If these forces see the light of day then working-class patriotic nationalism will be stirred up in places like the north. If this happens then it will be a whole different political world the Labour Party will find itself in.

In truth, I guess there is no simple answer, disempowerment, laziness to think, willingness to participate, misguided. I’m not sure; maybe these rent-a-slogans are desperate measures to scramble together a meaning, a notion of pride, loyalty or even identity in a world where borders are falling in a virtual world to access cheap food and goods, but increasingly pursued in a physical sense. Seeking protection like a boxer caught against the ropes, awaiting the knockout punch. The best, I feel, you can do on Election Day is remember your roots, the struggles of your parents to give you a better life. That one day you will be that older person reliant on care and support and if your family fail to step up, who will? It’s also about your integrity, values, and intelligence. A whole host of pound shop economists will tell you there is no alternative because, well you’ve guessed it, ultimately the prospect of change may disturb their status, wealth or power. Protection of the status quo is their priority, albeit they will tolerate a few crumbs to offset and polish over the harder edges. No matter how we may seek it, there is never any easy way to deal with complex problems. Compassion may not seem in fashion, but without it, we turn inwards, into a spiral of darkness, blaming those less fortunate.

In truth, I guess there is no simple answer, disempowerment, laziness to think, willingness to participate, misguided. I’m not sure; maybe these rent-a-slogans are desperate measures to scramble together a meaning, a notion of pride, loyalty or even identity in a world where borders are falling in a virtual world to access cheap food and goods, but increasingly pursued in a physical sense. Seeking protection like a boxer caught against the ropes, awaiting the knockout punch. The best, I feel, you can do on Election Day is remember your roots, the struggles of your parents to give you a better life. That one day you will be that older person reliant on care and support and if your family fail to step up, who will? It’s also about your integrity, values, and intelligence. A whole host of pound shop economists will tell you there is no alternative because, well you’ve guessed it, ultimately the prospect of change may disturb their status, wealth or power. Protection of the status quo is their priority, albeit they will tolerate a few crumbs to offset and polish over the harder edges. No matter how we may seek it, there is never any easy way to deal with complex problems. Compassion may not seem in fashion, but without it, we turn inwards, into a spiral of darkness, blaming those less fortunate. Sitting behind the bluntness of North East folk and our landscape of gradually diminishing industries was a sense of identity, connectivity; some would say community and others would say solidarity. My parents, like their parents before them, were driven by a natural desire of love that is shared by parents from across the globe, for their children to live a better life to which they had experienced. It was a generation that had witnessed at first-hand war on home soil, the effects of absolute poverty, created a welfare system and the movements to resist the unacceptable forces of privilege. Politics for my parents evolved from the experience of actual daily life rather than top-down, textbook theories, but organic, imperfect, slow and at times frustrating. It was a pragmatic type of socialism that built social spaces. Social spaces with stable job’s, the council house I was brought up in, The Worker’s Education Association where I took evening courses, the working men’s club my father frequented, the bingo hall my mother enjoyed, the annually planned visit to the seaside and the Christmas pantomime by a local club.

Sitting behind the bluntness of North East folk and our landscape of gradually diminishing industries was a sense of identity, connectivity; some would say community and others would say solidarity. My parents, like their parents before them, were driven by a natural desire of love that is shared by parents from across the globe, for their children to live a better life to which they had experienced. It was a generation that had witnessed at first-hand war on home soil, the effects of absolute poverty, created a welfare system and the movements to resist the unacceptable forces of privilege. Politics for my parents evolved from the experience of actual daily life rather than top-down, textbook theories, but organic, imperfect, slow and at times frustrating. It was a pragmatic type of socialism that built social spaces. Social spaces with stable job’s, the council house I was brought up in, The Worker’s Education Association where I took evening courses, the working men’s club my father frequented, the bingo hall my mother enjoyed, the annually planned visit to the seaside and the Christmas pantomime by a local club.