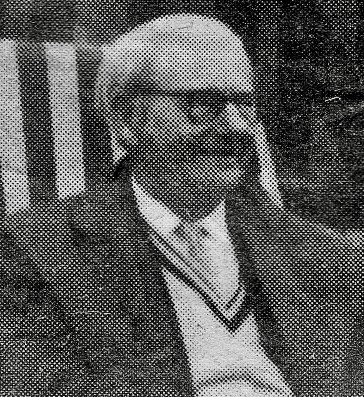

In my early political days, I had the good fortune to cross paths with people of remarkable conviction—individuals whose beliefs weren’t just ideas they carried, but the very compass that guided their lives. Among them was one man who left a lasting impression on me: George Short. He was more than just a politician; he was a living example of what it meant to stand firm in the face of hardship, to believe in something so deeply that no setback could shake it.

George had a way of cutting through noise and doubt, speaking with a clarity that came from both experience and an unshakable moral core. He lived his politics, not as a hobby or a passing phase, but as a lifelong commitment. I often think about how much I learned from him—not just about politics, but about courage, endurance, and the importance of staying true to one’s principles. People like George Short deserve to be remembered—not simply for what they did, but for the integrity and fire they carried into everything they fought for.

George Short was born in 1900 in the tough mining village of High Spen, County Durham. At just 14, he went down the pit, joining the ranks of thousands who worked the coal seams. But he was never content simply to endure harsh conditions — by the time of the great miners’ strikes of 1921 and 1926, Short was an active organiser. His role in those struggles cost him dearly: blacklisted from the coal industry, he would never work underground again.

Determined to keep fighting for workers’ rights, he served as a delegate to the Labour Representation Committee before joining the Communist Party in 1926 — a commitment that would define the rest of his life. By 1929, he was elected to the Party’s Central Committee, and years later he would serve on its Appeals Committee.

In 1930, Short travelled to Moscow, spending a year at the Lenin School and another working for the Comintern, even becoming a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. When he returned to Britain, he threw himself into building the Communist Party and leading the unemployed workers’ movement. His activism came at a cost: three months in prison, after insisting on the right to hold meetings at Stockton Cross.

The 1930s also saw him at the forefront of the anti-fascist struggle. After Japan’s invasion of Manchuria, he was instrumental in blocking the Haruma Mara from leaving Middlesbrough dock with scrap metal bound for Japan’s war effort. He helped stop the Blackshirts from marching through Stockton-on-Tees and took on the vital task of organising recruitment for the International Brigade in Spain.

After the war, Short remained committed to the cause of peace, supporting the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and, in later years, joining the re-established Communist Party of Britain. As President of the Teesside Pensioners Association, he launched a successful campaign for free concessionary travel for retirees — a victory felt by thousands.

George Short lived to the age of 94, passing away in 1994. His life was one of unbroken dedication to the struggles of working people, from the pit villages of County Durham to the global fight against fascism.

We need more Georges in our world today—voices of courage, hearts of steel, and a belief that change is worth fighting for.